–>

June 18, 2022

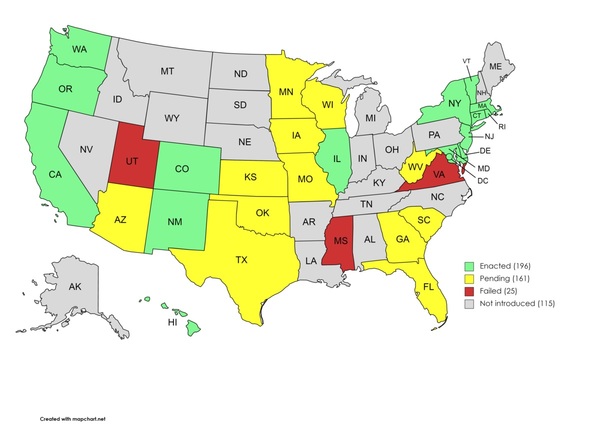

Fifteen states have passed similar legislation known as the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC). The compact will require each member state to award its electoral votes to the presidential candidate who receives the greatest number of popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Within each of those states, the compact will have no binding legal effect until any number of states whose sum equals 270 electoral votes enacts the legislation.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment invalidates the NPVIC because the compact treats similarly situated voters of separate jurisdictions differently when both cast votes for presidential electors in winner-take-all jurisdictions. Specifically, the NPVIC conditions the weight accorded a vote in one jurisdiction exclusively on the cumulative votes of all other jurisdictions to effect more political relevance to certain states.

No Legal Basis for Political Objectives

The case Williams v. Rhodes states intentionally dissimilar treatment occurs “…only if the classification rests on grounds wholly irrelevant to the achievement of the State’s objective.” Though the U.S. Constitution has granted explicitly to the states the power to appoint electors for President under Article II, Section I, Williams established that “these granted powers are always subject to the limitation that they may not be exercised in a way that violates other specific provisions of the Constitution.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Advocates of the NPVIC contend the “winner-take-all” system of electing the President in 48 of the 50 states and the District of Columbia provides a voter “with a direct voice in electing only the small number of presidential electors to which their state is entitled.” These systems manufacture “artificial electoral crises even when the nationwide popular vote is not particularly close.” The adverse impact leads candidates for President to campaign only in states “where the outcome is a foregone conclusion.”

Though persuasive, these arguments bear no legal relationship to a vote cast for the election of President. The political relevance of a presidential candidacy in the context of political realignments, public policy prognostications, or voting patterns should remain the province of campaign managers and political scientists. The NPVIC denies to each vote cast for President, regardless of jurisdiction, the equal legal value and protection guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution regardless of the jurisdiction’s present political designation as a battleground state.

Invidious Discrimination: Legal Standard

The standard established by the Supreme Court for Equal Protection under the Fourteenth Amendment regarding the right to vote permits the States to make classifications and does not require them to treat different groups uniformly. Classifications, however, must not arise from “invidious discrimination.”

NPVIC advocates contend that the decision by the Supreme Court in Williams v. Virginia State Board of Elections precludes interstate inequality as the basis for any suit regarding voting rights. In that case, the Court ruled that a winner-take-all allocation of presidential electors did not constitute interstate inequality. For purposes of election of the President, the decision merely acknowledges an unevenness in apportionment that is inherent to the Electoral College.

Bush v. Gore

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Two relevant points regarding right to vote enunciated by the Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, puncture a hole in the rationale  for the NPVIC:

for the NPVIC:

The right to vote is protected in more than the initial allocation of the franchise. Equal protection applies as well to the manner of its exercise. Having once granted the right to vote on equal terms, the State may not, by later arbitrary and disparate treatment, value one person’s vote over that of another.

Furthermore, the Court added:

The right of suffrage can be denied by a debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen’s vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise.

In McPherson v. Blacker, the Supreme Court recognized that an individual citizen “has no federal constitutional right to vote for electors for the President of the United States unless and until the state legislature chooses a statewide election as the means to implement its power to appoint members of the electoral college.” Thus, a statewide popular vote for President of the United States triggers a state requirement to provide equal protection.

The Supreme Court articulated that specific legal principle further in Bush:

When the state legislature vests the right to vote for President in its people, the right to vote as the legislature has prescribed is fundamental; and one source of its fundamental nature lies in the equal weight accorded to each vote and the equal dignity owed to each voter.

Practical Applications

Previous elections demonstrate the inherent discrimination that would result if the NPVIC had operated in the election for President. Al Gore earned more popular votes than George Bush, Jr. in 2000. Colorado, now a member state in the NPVIC, pledged its electors for George Bush. Connecticut, also a member state, pledged its electors for Al Gore.

The terms of the NPVIC would have treated the electors pledged by direct election of the people under a winner-take-all election in Colorado different from a vote for a Presidential elector for Al Gore in Connecticut under the same circumstances. The NPVIC would have nullified the votes of the winner, Bush in Colorado, because the compact conditions the determination of which slate of electors to certify based solely upon the vote tally within another state.

Similarly, a compacting state in which any third-party candidate earns the plurality of votes through a direct election by the people, as occurred in 1968, would engage in invidious discrimination. The compacting state would be bound to send its slate of electors in support of the candidate who received the most votes nationwide rather than the one for whom, under a winner-take-all system, should represent its interests in the Electoral College.

Solution: Constitutional Amendment

NPVIC proponents proffer the intent of the compact is to “…reach true democracy in our presidential elections not by eliminating the Electoral College, but reforming our use of it.” In actuality, the NPVIC would intentionally disregard all votes legally cast for all but one candidate by nationalizing the body in the U.S. Constitution — the Electoral College — specifically designed to represent the states in the election of the President.

The proper remedy, a constitutional amendment to eliminate the Electoral College, would acknowledge the U.S. Constitution as the supreme law of the land. A compact among states raises legal questions to circumvent the amendment process raises questions of law and political motivation.

Furthermore, a successful amendment process would remain federal in character by representing states, account for regional differences, and reflect a national consensus. Supporters have either knowingly masked their political objectives in legal arguments or truly cannot distinguish between them. They should heed the instructions provided in Williams v. Virginia State Board of Elections:

…we are of the opinion that a compulsory compliance with their demand or any other proposed limitation on the selection by the State of its presidential electors would require a Constitutional amendment.

Image: Minas

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to helpdesk@americanthinker.com

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>