–>

April 3, 2023

Texas state representative Bryan Slaton introduced a bill, on the 187th anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, to allow Texans to vote on seceding from the United States. Yes, secession, as in the pre–Civil War abandonment. Slayton said in a tweet, “After decades of continuous abuse of our rights and liberties by the federal government, it is time to let the people of Texas make their voices heard.” In fact, history teaches us that there are a few ways that this movement may be successful even without secession.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

First the history. Most Americans may believe that this war was already fought and even that secession is not a legal course forward, but a little research proves that the question is far more complicated than it first appears. One need look no farther than the aftermath of the Civil War to see the seeds of doubt.

As legal historian Cynthia Nicoletti of the UVA School of Law notes in her recent book, Secession on Trial: The Prosecution of Jefferson Davis, it was far from settled law even in 1865, on the heels of the Civil War. She concludes that none of the Confederate leadership was prosecuted for treason because it was a real possibility that their actions were not illegal. The nation and the administration simply could not risk a finding by the federal courts that the war they had just completed was illegal and that the thousands of dead had been killed by that illegal act.

Article 1, section 10 of the U.S. Constitution says nothing about a prohibition upon the states to secede, nor does Article 1, section 8, which enumerates the specific powers of the federal government. However the Tenth Amendment in the Bill of Rights does state, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This would, on its face, seem to include the right of secession as being reserved to the States or the people.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Roll the clock back a few decades before what many Southerners still refer to as the War of Northern Aggression, and we find that as early as the 1820s, serious discussion of secession was before the US Congress. In 1833, in response to South Carolina’s nullification of federal tariffs, Andrew Jackson signed his “Force Bill” into law. However, Jackson knew that threats of military force might lack the force of law and that threats alone could not maintain the Union, so he also reduced the questioned tariffs, essentially forestalling secession for few decades while recognizing that he had only cooled the simmering pot, not removed it from the fire. As Greg Jackson, M.A. notes in a study blog post on secession, “Jackson knew that the tariff issue was merely a pretext.” Jackson predicted that the issue of secession would come up again, since “disunion and southern confederacy” were the real objectives. He also said, “The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question.” Jackson was prescient, and for the next three decades, various compromises would attempt to forestall disunion without an invading army.

In 2021, the same issues plague conservative values, and the battle between states’ rights and federal rights continues. Texas seems to be taking a page from South Carolina’s playbook with the realization that a vote on the topic will force the conversation that the federal government was willing to start a war to avoid.

As with all governments, the U.S. federal government has an inherent, unhealthy addiction to power and greed. Those on the federal government’s side recognize that there is no position of power in this discussion and that the outcome of a legal contest on the issue is far from a secure win for their position. Let’s face it: even war is preferable to losing power and access to other people’s money.

It would be remiss in an article on this topic not to discuss the oft cited case of Texas v. White (74 U.S. 700, 1869) in which SCOTUS stated that the secession of the states was not legal, and therefore, Texas had never ceased to be a state of the United States. This decision, written in 1869 just a few short years after the surrender at Appomattox, is disputed by several legal scholars as bad law. In fact, the opinion references the Articles of Confederation and attempts to distinguish that union from the U.S. Constitution while simultaneously using the foundation of the Articles for its logic. The resulting opinion of the Court has been described as a “tortured decision” to use a commercial sale of bonds case to justify the Civil War or at least avoid condemning it as illegal.

According to polls, it seems that over 60% of Texans believe in a strict interpretation of the Constitution — a very limited federal government that, they would argue, is as the founders intended. They also believe, based upon the post, tweets, and releases of the grassroots orgs pushing for a secession vote, that the orders of federal courts must be followed by all, including the federal government in general and the Executive Branch specifically. Their claims are not baseless.

At the end of World War 2, there were only about 50 countries in the world. In 2000, that number had grown to 195, largely as a result of countrywide referenda to leave the conquering and colonial powers of yesteryear. The Biden administration and the U.S. government might be wise to take heed and have the discussion as opposed to the alternatives.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Texas will do the nation a service if it passes this bill, but probably not by secession. We can only hope that the current politicians will be as wise as Andrew Jackson, because we have clearly seen the result of the intransigent attitudes that would prevail in 1861.

Finally, It should also be noted that at least 18 states, as of this date, have committees, legislative groups or people working at the grassroots level, to consider or work toward secession. As goes Texas, will they also?

Michael Ange, Ph.D., a semi-retired consultant, author of 10 non-fiction books and hundreds of periodical articles published on three continents, has long been a student of the law studying at universities in the U.S. and the U.K.

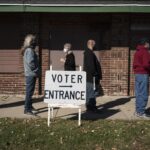

Image: Don Hankins via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>