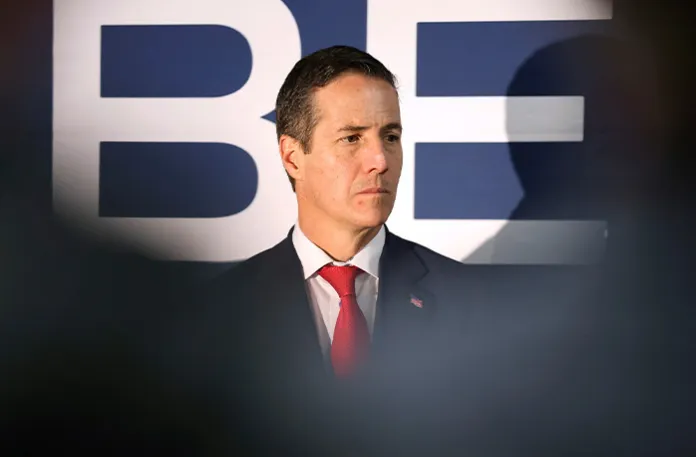

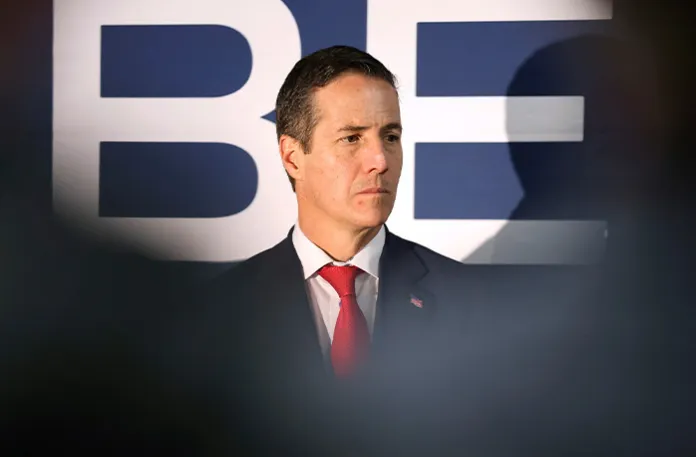

A bill that would make it illegal for Americans to be citizens of another country is causing anxiety for millions of dual citizens living in the United States and abroad. Introduced by Sen. Bernie Moreno (R-OH) on Dec. 1, 2025, the Exclusive Citizenship Act of 2025 seeks to establish that U.S. citizens “shall owe sole and exclusive allegiance to the United States.”

If passed in its current form, something legal experts say is unlikely, the legislation will automatically strip dual citizens of their U.S. citizenship should they fail to renounce their additional citizenship within 12 months of the law’s enactment, an act with far-reaching legal and tax ramifications.

There’s no exact count of American dual citizens because the U.S. government doesn’t track them. But estimates suggest that over 40 million people — more than 10% of the U.S. population — are eligible or possess dual nationality. That eligibility often comes through ancestry, sometimes extending to grandparents or even great-grandparents. Popular examples include Canada, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the United Kingdom, and various Latin American nations such as Argentina and Brazil. In those cases, eligibility depends on specific country laws and family lineage.

As of May 2025, 63 countries permitted dual citizenship with the United States, a 45% increase compared to 1990.

Many high-profile Americans hold dual citizenship, including first lady Melania Trump and first son Barron Trump (both of Slovenia), per Mary Jordan’s 2020 biography, The Art of Her Deal: The Untold Story of Melania Trump. There’s also Tesla CEO Elon Musk, an on-again-off-again-somewhat on-again supporter and political ally of President Donald Trump. Musk has citizenship from South Africa, where he was born, and from Canada by descent through his mother; he became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2002. Plus, a growing number of A-list actors with dual citizenship, such as Tom Hanks (Greece) and George Clooney (France).

Moreno, 58, was born in Bogotá, Colombia, and moved to the U.S. as a child. He became a U.S. citizen at 18 and renounced his Colombian citizenship.

Dual citizenship creates conflicts of interest, Moreno said in a statement when he introduced his bill to ban it.

“It was an honor to pledge an Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America and ONLY to the United States of America!” Moreno said. “Being an American citizen is an honor and a privilege — and if you want to be an American, it’s all or nothing. It’s time to end dual citizenship for good.”

Eroding the 14th Amendment?

The State Department’s website spells out clearly that, under current U.S. law, dual citizenship is allowed.

“U.S. law does not require a U.S. citizen to choose between U.S. citizenship and another (foreign) nationality (or nationalities),” the State Department notes. “A U.S. citizen may naturalize in a foreign state without any risk to their U.S. citizenship.”

Critics of the dual citizenship ban legislation view it as an attempt by congressional allies of the Trump administration to paint dual citizens as a threat to national security and thereby justify the erosion of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. The Reconstruction-era amendment, a cornerstone of American civil rights, grants citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the U.S., including formerly enslaved people.

When it comes to dual citizenship, “I’m completely convinced that there is a concerted effort by the current administration and its friends in the Senate and Congress to attack the 14th Amendment,” said Derek DeCosmo, a New Jersey-based immigration attorney. “On the president’s very first day in office, he signed an executive order to end birthright citizenship” for most children born in the U.S.

DeCosmo called Moreno’s bill “a legislative solution to a problem that doesn’t exist.” When people become naturalized U.S. citizens, “they swear allegiance to the U.S. There is nothing nefarious about wanting to keep the passport of their country of birth. People want to be able to enter and exit their home country and to inherit property.” Nor is there reason for concern when an American moves abroad and applies for citizenship in their adopted country, he said.

Those who would be affected include naturalized U.S. citizens who retain their original citizenship; the U.S.-born children of non-Americans who automatically receive both citizenships when they are born; Americans who obtain another citizenship when they relocate abroad or for any other reason; and Americans who marry a foreign national and must accept the spouse’s citizenship under that country’s legal system.

Keith Redmond, a co-founder of the organization Stop Extraterritorial American Taxation who advises overseas Americans about their rights, said the Moreno bill fails to address several key issues.

“There is no critical thinking put into this bill,” Redmond said, starting with whether Americans who have no choice but to renounce their U.S. citizenship under the bill would still be able to freely enter and exit the country, maintain a business, a residence, bank accounts, and investments. Would former Americans receive their Social Security benefits and retired military pensions? Would they be expected to pay a hefty ($2,350 in 2025) renunciation fee and a possible exit tax?

Redmond, a dual American-French citizen who lives in Paris, also balked at Moreno’s claim that Americans cannot be loyal to two countries.

“If a mother has two children, does she have more allegiance to one more than the other? That mother loves both her children.”

David London, CEO of the Association of Americans & Canadians in Israel, said the U.S. citizens he knows who also hold Israeli citizenship “are patriotic Americans” with a valid stake in both countries. Many are retirees who worked and lived in the U.S. for decades and still have assets and family there. Others commute to work or continue to work remotely for American companies. Like every other American living abroad, they must still file an annual U.S. tax return and are subject to American taxation laws.

If the bill passes, “it could create a serious problem and limit professional opportunities,” London said.

Sanford Levinson, a professor at the University of Texas Law School, believes that Moreno’s bill has virtually no chance of becoming law, given the Supreme Court rulings and legislation that have preceded it.

Still, Moreno’s bill “really does raise fundamental issues about what it means to be a citizen,” Levinson said. “At one time, if you fought in a foreign army or voted in a foreign election, you automatically lost American citizenship. But the Supreme Court said stripping citizenship for these reasons is unconstitutional.”

Accusations of dual loyalty don’t begin and end with citizenship, he noted. “Is ethnic loyalty a challenge to general political loyalty? This is an issue in any ethnically divided country.”

TRUMP TARGETS RAYTHEON AS ‘LEAST RESPONSIVE’ CONTRACTOR TO DEPARTMENT OF WAR

It was accusations of dual loyalty that enabled the U.S. government to imprison over 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent following the 1941 Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, and which fuels allegations “that the true allegiance of Jews is to their fellow Jews and that therefore they are inherently disloyal citizens and cannot be trusted,” according to the American Jewish Congress.

“This human dimension highlights the practical issue of why this bill is unlikely to pass,” Levinson said.

Michele Chabin (@MicheleChabin1) is a journalist whose work has appeared in Cosmopolitan, the Forward, Religion News Service, Science, USA Today, U.S. News & World Report, and the Washington Post.