As Democrats and Republicans pitch their hot-button talking points this election cycle, voters in Nevada might want to hear a little more about one issue that hits even closer to home: Housing.

Nevada is facing some of the highest housing prices in the nation. Debate around how to solve it comes down to a fundamental difference in worldview. Will more regulations, rent controls, and federally subsidized affordable housing fix the problem? Or is expanding free market solutions the answer to bringing down housing costs?

Nevada’s housing shortage is caused, in part, by a flush of new residents, many from neighboring California. Since 2020, 158,000 Californians have flocked to Nevada, now making up 43% of all new Nevada residents in the last four years. Additionally, the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles states that approximately 250,000 Californians moved to Nevada between 2015 and 2019, which was more than any other state. Ironically, although many Californians left the Golden State in search of cheaper housing, Nevada’s housing prices have soared as the supply of housing has failed to keep up with the increasing demand.

Last year, Nevada governor and then-gubernatorial candidate Joe Lombardo said his state was short at least 84,000 housing units, saying Nevada is “last in the country for its number of affordable and available rental units.” A 2022 study by the Bipartisan Policy Center found that while Nevada’s statewide population had increased by nearly 434,000 residents from 2010 to 2020, the housing supply had grown by only about 131,000 homes.

In response to a dwindling supply of homes, housing prices have soared. Redfin states that Nevada’s home prices were up over 7% from last year in May. Since 2016, home sale prices in Nevada’s Clark County have risen by 50%, and median rental prices in the county, which is home to Las Vegas, are still 30% higher than they were before the pandemic, according to Apartment List. A University of Nevada at Las Vegas study also found that seven of the 10 most common jobs in Las Vegas don’t pay enough to afford a studio apartment.

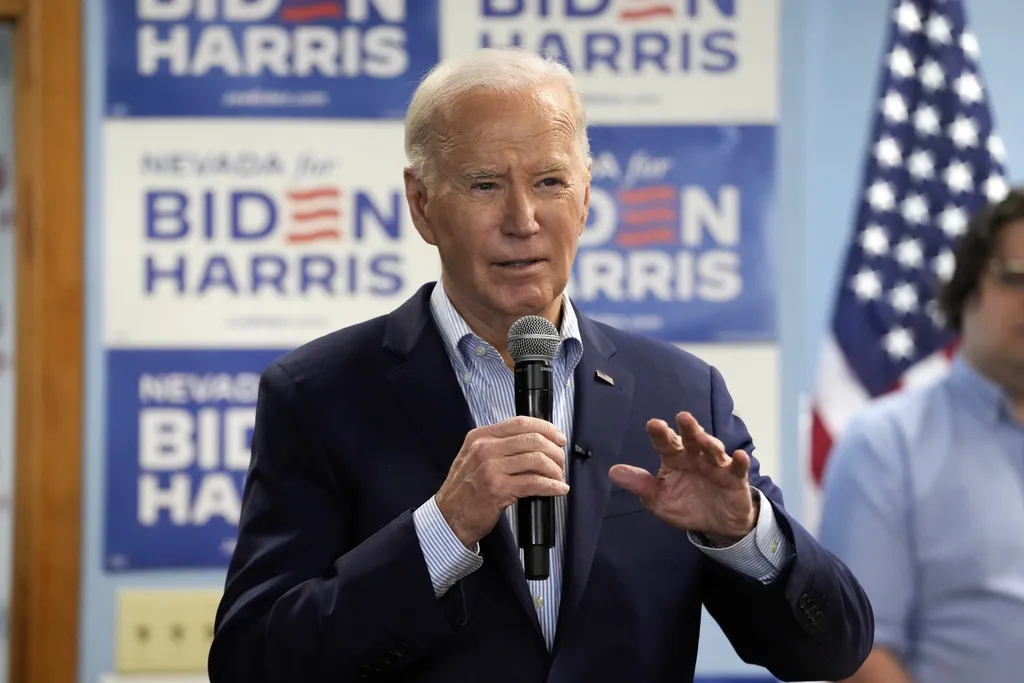

There is a unanimous consensus that Nevada’s soaring housing prices are driven by an imbalance of supply and demand. In March, President Joe Biden said at a Las Vegas event, “To solve [housing shortage] long term, we have to increase supply because when supply is down, demand is up, costs rise.”

“The bottom line to lower housing costs for good is to build, build, build,” he said.

The debate begins with the kind of housing to build and who will pay for it.

In Nevada, the Biden administration, and some of the state’s top elected officials have focused on building federally subsidized affordable housing. President Biden’s American Rescue Plan allocated $1 billion towards bringing down housing prices in the Silver State, $700 million of which was directly targeted to support major affordable housing projects. In Nevada’s Clark County, where housing is the hardest to afford, Biden’s subsidies have resulted in several pending major 200-unit affordable housing developments.

Ahead of Biden’s March visit to Reno, he announced plans to expand “tens of thousands” affordable housing units “right here in Nevada” by expanding the Low-Income Housing Tax Credits. The program, which subsidizes developers for building affordable housing, would direct $20 billion to build affordable multifamily units across the country.

Is building more affordable housing units going to bring housing prices down in Nevada? Roger Valdez, Director of the Center for Housing Economics and a Research Fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity told the Washington Examiner, “We don’t need more affordable housing. We need more housing so it’s more affordable.”

The more money the government adds to the housing market with affordable housing subsidies, the higher prices will be, Valdez said, adding, “That’s the basic rule of economics: more money means more inflation.”

Nevada’s governor echoed Valdez’s concerns about the Biden administration’s strategy to pour money into the housing market. In April, Gov. Lombardo said the Biden administration’s “excessive” federal spending” was contributing to soaring inflation and high inflation rates.

At the time, Lombardo said the Biden administration’s failure to embrace the free market was at the heart of what is driving the housing shortage, and “tearing at the very fabric of our state.” “Mr. President, it is time for your administration to embrace free market principles that rely upon supply and demand and rein in excessive federal spending that is hurting Nevada families,” the governor begged.

Valdez fears that, from zoning regulations and rent controls to affordable housing mandates funded with taxpayer dollars, the government’s efforts to lower housing pricing are having a counter effect.

“[The government says] let’s dump money on it [ the housing crisis]. Let’s create an entitlement program called affordable housing, where we build housing and then charge less for it. But the problem is that the pace of construction of those affordable housing units can never keep up because it’s even harder to build, because it’s even more regulated than the market rate housing. So what we end up doing is, we create all these constraints and limits on what can be produced. We artificially create higher prices, with the regulation, and then we complain about it,” Valdez told the Washington Examiner.

Lombardo has brought up another issue he says contributes to Nevada’s high housing prices. He blames intensive federal ownership of Nevada’s land as part of the factor contributing to high housing prices. The federal government owns over 85% of Nevada’s land. The governor says “by making federal lands available, Nevada could increase its housing supply and address shortages, which would ultimately drive down costs.”

Valdez agrees that while land is important, it’s not the biggest factor at play. “It’s primarily zoning and regulatory overreach that limits and increases cost,” the housing expert told the Washington Examiner. He says imposing more regulations creates a vicious cycle. When residents are unhappy with housing prices, the government steps in to try to lower them by imposing rules on landlords, builders, and developers. Valdez says this drives the cost of production even higher, disincentivizes builders from creating new housing, and creates even higher prices.

In a statement to the Washington Examiner, housing expert Halley Potter agreed that zoning regulations drive up housing prices.

“Exclusionary zoning policies artificially drive up housing prices by limiting the construction or conversion of more affordable homes such as apartments and backyard cottages,” said Potter, a senior fellow and director of PK-12 education policy at The Century Foundation.

During an interview with the Washington Examiner, Potter argued that eliminating exclusionary zoning should have broad political support. “There’s a really strong libertarian case for getting rid of exclusionary zoning that determines who can build what, where. There’s also a progressive case to get rid of exclusionary zoning because it is unfairly locking low-income families out of different neighborhoods,” Potter said.

Rent controls are another option Nevada’s elected officials have considered to offset rising housing costs. In 2022, then-Governor Steve Sisolak decided that was the best course to bring housing prices in Nevada. At the time, the median price of a home in Las Vegas in May was $482,000, up 25% from 2021, and the median price of a home in the Reno/Sparks area was $605,000, up 23% from the previous year. The governor threw his support behind a ballot measure to limit rent increases to a maximum of 5% or the cost of living, whichever was less, saying, “I think there’s an awful lot of support for this. And if I’m right, and the people do support it, we’re going to be addressing this in the [legislative] session.”

Valdez says while price controls sound good in theory, in practice, they don’t play out so well.

“Price controls always have the effect of creating inflation. Because what happens is it disincentivizes production, but then lack of production causes scarcity prices to go even higher,” the housing expert said. “And then the higher prices rationalize the offset [more rent controls].”

Valdez believes that the solution to the housing crisis is to introduce choices to the housing market. According to Valdez, choice breeds competition, and competition drives prices down. He says this can only happen when regulators get out of the way. “The easiest way to solve [the housing crisis] is to get out of the way of the production, and then people will be able to have better leverage over the market because they’ll have more choice.”

“With housing, we’ve regulated in such a way that your choices are so limited and that includes what you’re going to pay for it,” Valdez said during an interview with the Washington Examiner. “So we just need to get out of the way of the limits to production, increase supply, incentivize more supply, and then we’ll see prices rationalize.”

Potter disagrees. When the Washington Examiner asked her if freeing up developers and builders to create more market-rate housing would drive prices down, she said it would take too much time. “I think we need something that can happen faster,” she said. “That means continuing and expanding some of the programs to have explicitly inclusionary zoning and affordable housing requirements that are embedded into development.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Valdez agrees that allowing the market to run its course takes time and that freeing developers and builders to build market-rate housing is unpopular. “When you’re trusting the market to produce more, it not only takes time, but it’s uneven,” Valdez told the Washington Examiner. He says the hustle to gain voters’ favor with immediate and tangible solutions pushes elected officials to an easy way out. “Politicians can get in front of the big ribbon and cut the ribbon and watch people moving into [affordable housing units] and say, ‘I did something to solve this problem,’” Valdez said.

A recent poll found that 51% of Nevada residents considered housing to be very important going into the presidential election, more than issues including abortion, climate change, the Russia-Ukraine war, or guns.